I’m on the Osaka subway and it feels home.

Getting back into the flow now, adjusting to the speed of people, the precise timing of ticket gates, changing subway on autopilot mode while writing emails, fitting in the dynamics of train queues, instinctively buying a new drink when the last one is finished.

Coming to Osaka helped; the city is huge but subtly different from Tokyo. People here don’t look as stressed, serious, extreme: businessmen wear their suits slightly looser, girls are just as charming but one step away from the ultimate fashion festival that permeates the streets of the capital, people bike around. And of course, they stand on the other side of the escalator.

For lunch, I followed a friend’s recommendation: ichiran (一蘭), a ramenya chain present in Dotombori. His advice is accurate: it is one of the most excellent ramen I ever ate. However, the place is also a prime example of Japanese culture.

As I enter, a waitress welcomes me and invites me to buy the ticket for my food. I just pick a ramen (750¥) but one can also order extra noodles, garlic, beer, etc. She then tells me the number of my booth.

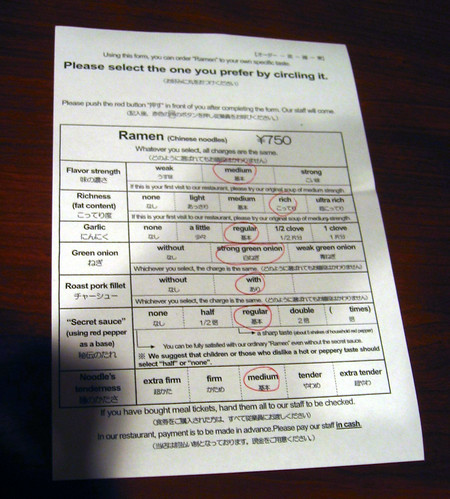

Every customer eats in his own booth. They are arranges as a line, less than twenty of them. I sit down at number 10 and fill the form that has been prepared for me (after having asked for the English one, to avoid any translation bias for this first time). I can choose the flavor strength, the quantity of garlic, of special sauce, the tenderness of the noodles, etc. I ring the bell and a waitress comes to take my form and ticket, through the opening in front of me. I don’t actually see her face, except when she bows.

The serving is about as instantaneous as humanly possible. I hardly had the time to help myself with water a the tap of my booth. As soon as my bowl is served, they close the opening with a curtain to let me concentrate on the ramen. Which, naturally, is delicious.

You leave when you are done, since you already paid. The whole thing can literally be over in under 5 minutes.

I would expect most Westerners to be utterly shocked/amazed by the experience. Nothing comes even close to it in the Western world. Even McDonald’s McDrive would suddenly feel like a socially rich gourmet buffet, immediately disqualified from the “fast food” department.

However, I’m pretty sure nothing of the sort existed even in Japan only a few decades ago. Today, it is by far not a special case; I cannot begin to count the number of culture-stretching artifacts I encountered in Japan. The truth is, if the Japanese were to be deeply shocked/amazed by each and every one of them, they wouldn’t last long. Trucks of mind-blown corpses would leave Donki Hote’s über-bazaar every day.

Somehow, either through antique wisdom or natural adaptation, the Japanese seem to cope with culture-bending changes uncommonly smoothly. Mind you, they remain equally conservative politically, or towards local foreigners, women or workers’ rights. But when it comes to offering a pragmatic service, all ideas break loose.

There is an incredibly vigorous and widely accepted drive to exploit all possible improvements to Japan’s rather rigid and streamlined way of life: the inhibition-free entertainment of karaoke; the round-the-clock practicality of ambient convenient stores, bento and vending machines; the optimized workflow of public transports, restaurants or capsule hotels; the dedramatization of sex through love hotels; the ubiquitous information available on mobile phones. As if here, the purpose (is it wanted/useful?) of inventions won over their perception (is it weird/wrong?). The study of how a whole set of values is allowed to evolve so quickly while other values are rigidly maintained, sometimes against all imaginable variations of common sense, is left as an exercise to the reader.

What I believe we as foreigners could learn from this is the dynamic, (locally) open-minded approach of daring to ask “what if…?” before trapping new ideas into a conservative framework of values. It is the curiosity to play with original concepts and accept to take the risk to see it fail.

Or, to abuse the hope/fear dichotomy of the upcoming American presidential elections, it is gathering the courage to question your values to do what is needed and fun, rather than fighting to get back to an imaginary state of stability.