The very first taste of Sapporo I get is the corn-butter-miso-ramen I order in a tiny restaurant in the “ramen alley” next to the neon-light festival of Susukino.

This variant, specific to the northern island of Hokkaido, could be described as the final boss of the noodle soup family, the Mother of all Ramen. Delicious though not as unarguably heavenly as the ramen I had in ichiran, this miso ramen is heavy, imposing, almost daunting in its richness. I slurp the very last drop of it.

Yummy corn-butter-miso-ramen, by theefer

Yummy corn-butter-miso-ramen, by theeferTo celebrate the victory, I wander in the streets of Sapporo for a while. The temperature has dropped with the night and the higher latitude. I reach Odori and stop to observe the illuminated silhouette of the local Eiffel Tower replica, overlooked by the full moon. A couple of young people break-dance to the sound of Japanese hip-hop on the paved alley of the gardens leading to the tower.

The next day is dedicated to a touristic visit of the city: the Nijo fish market (for a tasty salmon oyakodon), the Sapporo Beer Museum, the botanical garden, a small museum on the ainu culture (the Aborigines in northern Japan), the modern art museum, the tall ferris wheel that oversees the whole city at night.

Sapporo Beer Museum (formerly brewery), by theefer

Sapporo Beer Museum (formerly brewery), by theeferBy chance, I also drop by an ainu craft shop later, where I learn a bit more about their culture from the owner, a friendly ainu woman. Hunger hits again right after that and I’m off to a random kaitenzushi to taste some fresh sea food: scallops, shrimps, crab, various fish.

Ainu decorated bear skull, by theefer

Ainu decorated bear skull, by theeferThen I walk back to the blinking neon walls of Susukino and spend some time watching the ballet of taxis and crowd sharing the crossing, the parade of elegant boys and girls passing by, their fashion subtly lending to warmer clothes. Although reminiscent from similar blinking-at-night neighborhoods in other cities, there is an imperceptible Hokkaido touch in the mood here, of freshness, rurality, nature, perhaps linked to a more recent and less total urbanism.

I am barely even hungry when I go for my second diner, but I am decided to taste another local specialty, the Gengis Khan (jingisukan). I pick a tiny restaurant in the outskirts of the popular areas, with less than 10 seats, all directly at the counter. Soon, I’m grilling my lamb and vegetables on the charcoal grate in front of me.

Gengis Khan (grilled lamb), by theefer

Gengis Khan (grilled lamb), by theeferAs other customers arrive, we engaged in a friendly discussion about Sapporo and Japan, and the unavoidable questions about what a Swiss guy is doing there and why I don’t speak Japanese with a Kansai accent although I lived for 6 months in Osaka. We’re all equally curious about each other’s culture.

I love such authentic venues, a traditional Japanese setting where customers and vendor alike feel at ease to share a moment. Yet, although the atmosphere is obviously more relaxed than the one in a commercial chain restaurant, there remains a strong respect both ways: towards the chef, who is often referred to as “master”, and towards the customers, served and attended to with great care.

It took me a while to come up with a sociological model for the ubiquitous politeness in Japan.

Ramenya in Sapporo, by theefer

Ramenya in Sapporo, by theeferIn this model, the Japanese roleplay. Not occasionally as a game; they roleplay their job, their personality, their life. At work, they adopt the role required of their job, without concession. That must be what the West tries to signify by saying that “the Japanese live for their company”.

Personally, I perceive it more as a trait of a culture where the norm is to accept one’s role and play it, as best as possible, possibly to the detriment of one’s “self”. Naturally, the performance sometimes persists outside of the work environment, but there always remains a level of self-awareness, which for instance materializes when people describe the hard work required by their work. However, the discipline usually keeps them from rebelling, as if their role took precedence over their individuality. This implies one popular solution to strong conflicts: changing one’s role, either by quitting or relocating in one’s company.

Old Sapporo Beer posters, by theefer

Old Sapporo Beer posters, by theeferHowever, roles are not unique, but superposed. On the street, for instance, people adopt a more neutral role, especially in the metro where the activation of a quiet, absent-eyed character might evoke some sort of sinister resignation. I’d rather view it as a modern role, that of “the passenger of public transportations”, invented solely to ensure the comfort and effectiveness of crowded shared spaces.

Or picture someone crossing you in the street, successfully engaged in the neutral role of not noticing your existence until you request his attention (”sumimasen!”). Then, most of the time, after a short transition of surprise, the person will switch to a different mode, that of an absurdly helpful person.

People & Taxis in Susukino, by theefer

People & Taxis in Susukino, by theeferLuckily, in addition to such practical social roles, people also develop their own personal role. I believe it remains a “role”, to be contrasted with our notion of “personality”, because it often remains more abstract, sometimes stereotypical. In particular, it seems to be common to have one extreme hobby, be it visiting all museums by bike, traveling all over the world to see one band play, collecting a specific type of items compulsively, or simply dressing up like the fantasy version of a European maid. In other words, unlike their personality (they also have one, of course), their individual role has been consciously crafted.

Given this large panoply of roles, the Japanese excel at switching, superposing and carefully picking the appropriate one depending on the situation. Such a dedication to a community-optimized form of roleplay constitutes much of the exoticism we perceive in the social interactions in Japan, and what distinguishes it from the much more individualistic philosophy we defend in the West, where identity is prime and committing to a role is almost considered as an obscene violation of freedom.

Sapporo Botanical Garden, by theefer

Sapporo Botanical Garden, by theeferWhile I like to play with this kind of psycho-sociological model, which could still be further explored, I don’t pretend it to accurately represent interactions in the Japanese culture. It is merely an idea, a “castle of the mind” built to explore an alien culture I find fascinating.

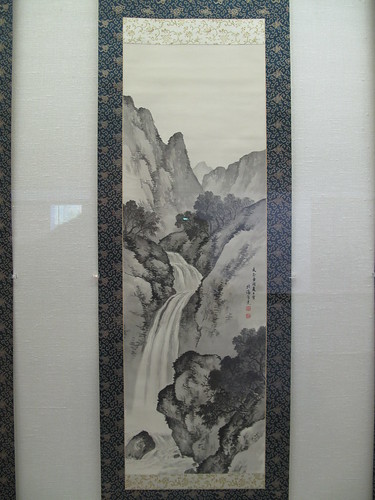

Painting (Sapporo Modern Art Museum), by theefer

Painting (Sapporo Modern Art Museum), by theefer